Your Cart is Empty

The Saga of 500d

March 14, 2019

The Saga of 500D

by Kevin Dee

Jack and I have both been working in sewn goods for some years now. We’ve been looking at textiles long before EVERGOODS, and it’s astounding to me how much there is to know. Of course, the textile industry continues to move forward, so it’s important to keep tabs on new innovations and technologies, but the more I work with fabric, the more I find myself also looking backward. Cloth is ancient, and there are a lot of steps involved in creating textile. With variables that can affect the finished material at every stage, the more I think I understand, the more I realize that there is more to learn about the basic nuts and bolts of cloth.

Raw material swatches/samples at the ready during design phases.

When we started envisioning the EVERGOODS product line we knew early on that there would be a more urban line and a more outdoor line and wanted to use high quality fabrics that were specifically suited to each. Jack and I have both spent significant portions of our lives living in large cities, and for our more urban “CIVIC” line we agreed that we wanted a rugged textile with a dull, matte appearance. Something durable and low key. Something that didn’t stand out too much, but was still very special.

I’m honestly not all that enthralled with typical backpack “Cordura”, but in this textile search it was an obvious starting point with its dull finish and tough reputation. So, we’re in a meeting with one of our fabric vendors, talking about this imaginary textile, looking at their backpack Cordura and other offerings. I’m staring at a pile of swatches, asking myself how I should even compare or evaluate them. Of course, it depends what the product goals are, and what you’re trying to understand about the fabric, but there’s no great answer. I just try to make whatever relevant observations I can and hopefully glean some sense from them. I feel it in my hand, feel it again as I wad it up in my fist and release it, look at it through a magnifying loupe, I don’t know. For some reason I decide to hold it up to the light and look at the back side. I can see tiny dots of light through the coating (which tells me that the fabric isn’t super tightly woven or heavily coated) but more interesting is that the dots aren’t evenly and randomly dispersed like I expected, they look more like waves of parallel lines. I ask the vendor why they appear so directional and learn that this textile has more yarns in the warp than it has in the weft. This is interesting. I ask if there’s anything with the same number of warp and weft yarns. He has to think for a minute and then starts rifling through a storage closet looking for some long-forgotten swatch. He comes back with an experimental development for the military from last decade. It’s really plain looking, but somehow also very beautiful. Smaller yarns, textured for matte finish, more densely woven, and with identical yarn count in the warp and weft (called a “balanced” weave). Now, you have to get in with a magnifier and count the yarns to confirm the weave, but once you know what you’re looking for you can actually see it with a close look. Balanced weaving has a boxy, grid-like surface texture, with no apparent flow or visual movement in any direction. It’s like this super-regular, static surface. It’s totally boring, and yet quite beautiful in concept and in appearance. It was perfect.

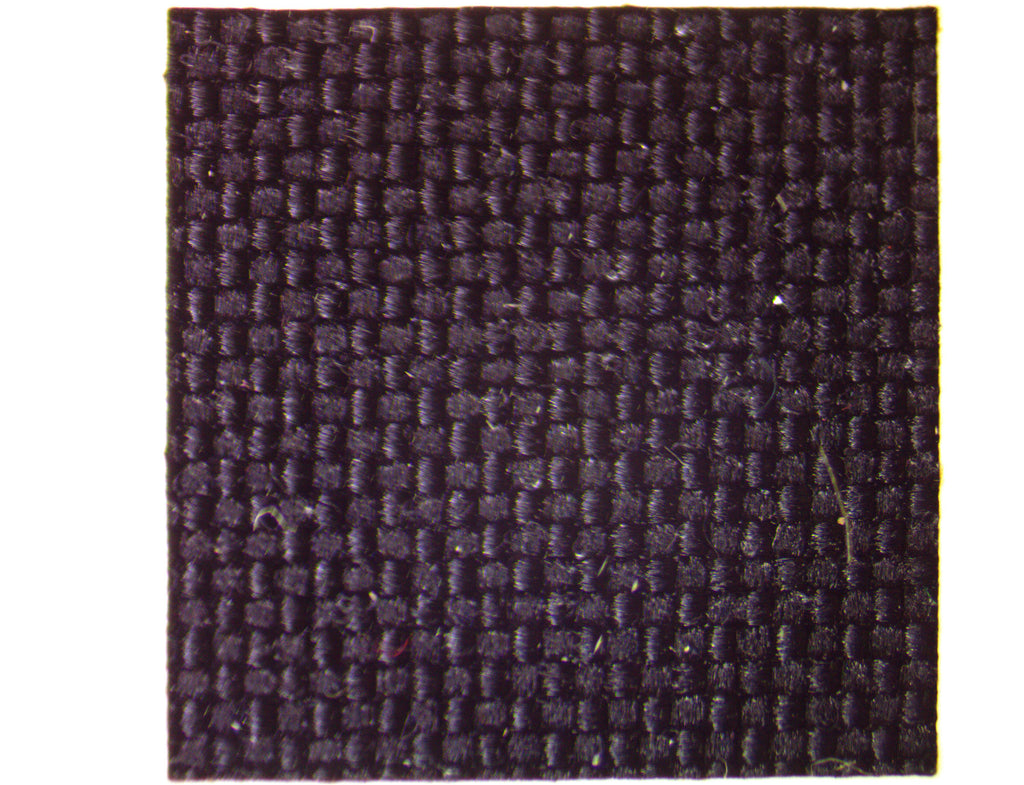

This balance woven 500D looks like a nearly perfect grid because it is woven evenly in all directions.

Man, we wanted that textile.

Unfortunately, this was someone’s abandoned experiment, not a running production item. The yarn that the textile was made from wasn’t being produced and would have to be created, and the vendor had no looms set up to do the weaving. In short, we would have to commit to government-sized volumes to get anyone to move on this. Jack and I were in no position to pursue this, but we were one step closer to realizing our CIVIC textile.

I understand now that warp-heavy weaving is actually quite common for reasons of cost. In addition to the material cost of the yarn that goes into the textile, another contributing factor is how much time it takes to complete the weaving. The warp beam (the vertical yarns) in a loom is only set up once for a fabric run, so if the mill packs extra yarns in the warp, it can get away with fewer yarns in the weft (the horizontal yarns). These weft yarns must be run back and forth with a shuttle, and with fewer shuttle passes to fill in the weft, the textile comes off the loom at a faster rate. This time savings equates directly to reduced cost in the finished material.

Non balance woven Cordura, what you typically see on the market place, is less expensive, has a courser hand feel, and does not have equal tear strength in both directions.

Here’s the question: “Does this even matter?”

For many products I’m sure that it doesn’t. I’m not entirely sure that it matters for backpacks, but it appeals to the Designer in me. There are many variables that can affect textile performance, but generally speaking these warp and weft proportions will affect tensile and tear strengths as well as seam slippage and bias stretch behavior, often improving performance in one textile direction, while weakening it in the other.

All of these variables can be managed and even leveraged through design. For example, a conveyor belt having disproportionately more strength along its length could make a lot of sense, especially if that made it cheaper to produce. But something like a backpack can be subject to all kinds of unpredictable forces and I’d rather work with a balanced weave fabric that behaves evenly and predictably across the warp, weft and bias. In addition, a textile that is essentially the same in both directions gives the cutting room more layout options and so consumes less fabric and creates less waste (though this material savings does not offset the increased weaving cost in the fabric).

We were excited at the discovery of this balanced weave, textured nylon, and also disheartened. Would we ever find a similar textile from another vendor? Or be able to convince a mill to custom weave a relatively small amount for our first backpack production? We attended trade shows and sat with every relevant vendor we could get a meeting with. Sure, balanced weaving can be done, but why? It’s more expensive and nobody wants more expensive. We needed a partner that was interested in doing high-end, not just high-volume, and we eventually found one. It was actually a similar scene. We started asking about balanced weave, textured nylon, and this vendor went to the storage rack and dug up some previous customer’s abandoned development. This time the yarns were a higher-grade Nylon 6,6, in a balanced plainweave construction with a substantial PU coating on the back and a silicone treatment on the face. It was visually beautiful, with a matte appearance and a firm hand that felt strong and exuded quality. Of course it was expensive, but the weaver said that the yarn was available and that he could produce it in a quantity that we could handle. There was still some leftover yardage on a shelf back at the mill and we requested some for our shop to do initial evaluation and prototyping. We left the meeting grinning ear to ear.

More expensive than other 500D Corduras, this balance woven nylon 6,6 fabric meets EVERGOODS fabric requirements. All Corduras are NOT created equally.

The textile arrived in an olive color. It was gorgeous. The fabric met all of our lab and field-testing criteria and we liked the water repellant and technical vibe of the silicone treatment. The field testing backpacks we made had even started to take on a nice waxed-canvas patina with use. We were totally smitten and approved this textile for our first production in late 2017.

By and large the response to this fabric has been overwhelmingly positive. It really is great! But there were also customer comments and blogger reviews noting that our backpack seemed to get dustier than others.

Dust?

Sure, we saw some dust pickup. But textured fabrics are always prone to that, and the olive color that we prototyped with didn’t really show this as a significant issue. By the time the mill ran pre-production yardage in our requested black color, EVERGOODS was screaming down the runway toward launch. The silicone’s affinity for dust was more noticeable in black, but we had already normalized this and committed ourselves to this material. Was this dust thing even real? Or were we just hearing some overly sensitive reviews, and then experiencing the echo chamber of internet chat rooms? It was hard to be sure, but we needed to find out.

Around this time we were working on the Standard Grey color for the new 2019 product. We contacted the fabric vendor and requested some of this 500d yardage with a standard water-resistant finish instead of silicone for comparison. The mill made a small batch and we used this yardage to build a “half & half” sample (a field-testing approach that I became familiar with at Patagonia) which is literally a simplified test pattern that gets seamed down the middle and made of two different materials to be evaluated side by side in identical conditions.

Silicone finish on left. Durable water repellent finish on the right.

Initial observations showed that the silicone-free textile picked up less dust when brand new. This was not a huge surprise, but month’s worth of work commutes, trail hikes and muddy mountain bike rides showed us more. Our neutral grey began to take on a subtle brown overtone on the silicone treated side. It appeared to be attracting and then retaining more dust and dirt than the non-silicone side. Further evaluation showed that the standard fluoropolymer-based finish was actually more water repellant than the silicone as well, both on virgin rolled goods and on our thoroughly thrashed half-and-half sample.

While both finishes are quite water resistant you can see after several minutes the water droplet on the left (DWR finish) is sitting more proudly (this proudness is a direct result of how water is reacting to the surface tension where it lies). Neither finish is allowing real absorption but the DWR treated side is the clear winner.

This was a revelation, and felt like one of those rare win/win opportunities. With improved soil and water repellency and no discernable downside, replacing the silicone with fluoropolymer was an easy decision. Thanks to everyone for their engagement and honest feedback about the product, it’s only making EVERGOODS better. If you made it this far, thanks for letting us share our 500d journey with you. “Getting it right” is a long road, and I have no reason to believe we’re there yet. In truth, I kind of hope we never get there. I’m starting to believe that the journey is all there really is. Thanks for taking the ride with us as we continue to build EVERGOODS.